A Primer on How Foreign Companies Pay U.S. Taxes

No stone is left unturned when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) collects taxes. Whether you’re a local business or a foreign company that wants to do business in the United States, you must follow the rules and pay taxes.

But the tax rules for domestic and foreign businesses differ, making it vital to know them for you to avoid penalties and make the most out of your available tax deductions.

It can be confusing what constitutes a foreign and domestic business and its associated taxes. The infographic below gives you an overview of everything to know if you’ve ever wondered, “Do foreign companies pay U.S. taxes?”

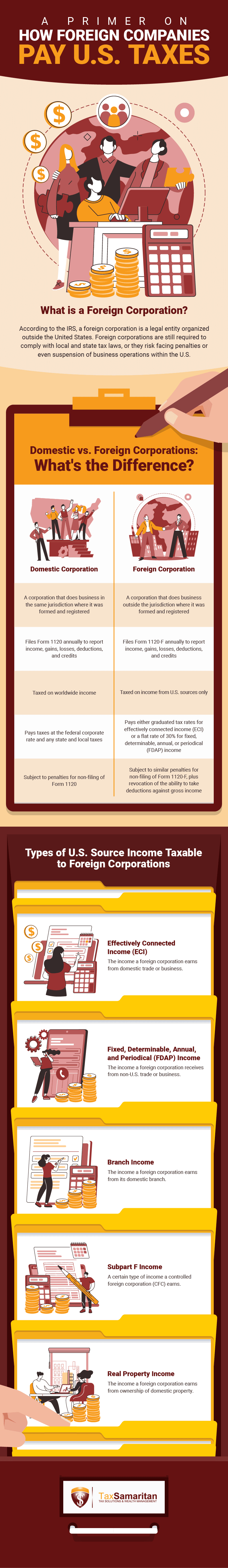

What is a Foreign Corporation?

There are two ways to define a foreign corporation, also known as an alien corporation. The first is by determining where it was registered. For example, a corporation in New York must register as a foreign corporation in California — a different state and jurisdiction with its own laws — despite both locations being within the United States.

The second approach to defining foreign corporations covers tax purposes. U.S. Code Section 7701 states that a corporation is foreign if it isn’t domestic. So, a business organized and registered in France but does business in the United States is a foreign corporation. Here, the concept of “doing business” applies if the corporation has an office, bank account, or representative in the United States.

On the other hand, controlled foreign corporations (CFCs) are foreign corporations where more than half of the shareholders are U.S. persons with at least 10% company ownership.

Foreign companies must comply with local and state tax laws or risk facing tax compliance issues and be liable to penalties or even suspension of business operations. As such, developing a clearer understanding of the difference between a domestic and foreign corporation is crucial.

Domestic vs. Foreign Corporations: What’s the Difference?

The nuances between the two types of corporations often make understanding them challenging. Read on to help you clarify their distinctions, specifically when filing U.S. taxes.

Domestic Corporation

A domestic corporation is a business formed and registered in its home state. Suppose a corporation’s establishment started in New York. Then it is a domestic corporation in that state. Should it expand its operations in California, it then becomes a foreign corporation in California.

However, the IRS views domestic corporations differently. U.S. Code section 7701 defines domestic as “created or organized in the United States” under U.S. laws. While a New York corporation may be a foreign corporation to the state of California, the IRS still considers it a domestic corporation.

Under domestic corporations’ tax responsibilities and guidelines, businesses operating in their home states must file Form 1120. Their worldwide income is subject to a 21% federal corporate tax. They must also pay any applicable local and state taxes.

The penalty for a domestic corporation’s late tax return filing is 5% of the unpaid tax for every month the return is late but cannot exceed 25%. The minimum penalty if the business is late for more than two months is the smaller of the tax due or $435.

Then if the corporation fails to pay its taxes on time, it could pay half of 1% of the unpaid tax for each month of non-payment up to a maximum of 25%.

Foreign Corporation

Foreign corporations follow a different set of taxation guidelines. While a domestic corporation needs to file Form 1120, a foreign corporation must file Form 1120-F instead. The tax rate foreign corporations must pay on their U.S.-based income depends on their income type.

Foreign corporations with effectively connected income (ECI) follow a graduated rate that applies to U.S. citizens and resident aliens. In comparison, those with gross fixed, determinable, annual, periodical (FDAP) income must pay a flat 30%.

Regardless of the income type, foreign corporations’ penalties for late filing and payments are equivalent to the penalties for domestic corporations. Additionally, foreign businesses need a U.S. Employer Identification Number (EIN) to file Form 1120-F.

The U.S. tax filing process for foreign corporations can quickly become overwhelming, especially when income comes from multiple sources. As such, knowing the different types of taxable income can smoothen the tax filing process for your company.

Types of U.S. Income Taxable to Foreign Corporations

Again, the type of income a foreign corporation earns while doing business in the U.S.determines how it will be taxed. Generally, two types of U.S. income are taxable: ECI and NECI (non-effectively connected income). Although, other types of U.S. income also exist.

1. Effectively Connected Income (ECI)

Effectively connected income includes income gained or lost over the tax year from sources within the U.S. It applies even if there’s no connection between the money earned and the company’s trade or business.

To illustrate, suppose your company’s location and registration are in Germany. Its office or establishment in the U.S. is known as a “material factor.” The income earned is taxable if the material factor generates money through regular operations.

ECI can also include transportation income, which you earn from using a vessel or aircraft to deliver services in the U.S. Here, ECI means your company generates income from the office that lets you trade or do business in the U.S. At least 90% of your transportation business’s earnings should be from regularly scheduled sailings or flights.

2. Fixed, Determinable, Annual, and Periodical (FDAP) Income

Fixed, determinable, annual, and periodical (FDAP) income is also commonly known as non-effectively connected income (NECI). What sets NECI apart from ECI is that it applies to all income except for the following:

- Income earned from the sale of real estate property

- Items of income excluded from gross income, such as tax-exempt municipal bond interest and qualified scholarship income

The IRS outlines the definitions for fixed, determinable, and periodical income as follows:

- Fixed income means you know how much you will be paid ahead of time.

- Determinable income means you have a basis for computing the amount you expect to receive.

- Periodical income means payments you receive annually or at regular intervals.

Common types of FDAP income include alimony, real property income, and fellowship funds, to name a few.

3. Branch Income

Branch income is the profit made by a foreign corporation’s U.S. branch. Its tax rate is 30%, although applicable tax treaties between the U.S. and the company’s home country may lower it. The IRS imposes this tax to treat foreign corporations like U.S. corporations.

However, since the U.S. has no legal authority to tax dividends paid by a U.S. subsidiary to foreign investors, the IRS subjects the branch’s income to tax after it has paid regular corporate income tax on its profits. You don’t need to pay tax on the remaining profit if you reinvest it in the company’s U.S. branch, but sending the profit to the home country will incur taxes.

4. Subpart F Income

Subpart F income refers to the earnings of a controlled foreign corporation (CFC). It includes income moved from one jurisdiction to another, insurance income, and foreign base company income.

Subpart F or CFC tax applies only to shareholders with 10% or more of the company’s stock or voting power. The tax is based on a proportion of their gross income from the CFC, regardless of whether the corporation retained the income or distributed it to its shareholders.

5. Real Property Income

If you own real property within the U.S. that generates income as part of your trade or business, that earning may be taxable.

Unlike branch income, real property income may not necessarily be an extension of your business operations. So, if you own a home and rent it out, you earn real property income.

Royalties you gain from mines, oil, gas wells, and other natural resources fall under this income type, as well. The same goes for the income you earn from selling or exchanging coal, timber, or domestic iron ore with its economic interest retained.

Comply with Corporate Tax Rules

U.S. tax policies for corporations are complex. You must first understand whether your corporation is domestic or foreign. If it’s foreign, you need to account for the different types of taxable income from your U.S. operations.

Neglecting to manage your foreign corporation’s taxable income comes with costly consequences and penalties. That’s why it’s worth working with such as Tax Samaritan to ensure you’ve covered all your bases when tax season is in full swing.

Tax Samaritan has been offering professional-quality tax resolution services to expats since 1997. We will work with you closely to ensure your organization stays tax compliant. Get a free tax quote from us today!